Principe Island looking south toward Rio Porco, site of the new discovery. A. Stanbridge phot.

The birds of São Tomé and Príncipe are truly spectacular and by rights should be a major birdwatchers tourist destination. The island avifauna is probably the best understood of the terrestrial vertebrates and since our research concentrates on poorly known species, our expeditions have never included an ornithologist and the incredible bird life appears only occasionally in this blog. Recent events require further attention.

Birds have fascinated amateurs and scientists alike from very early on in the history of science; because of this strong and enduring attention, the discovery of new, undescribed bird species is rather infrequent and thus quite exciting.

The Principe scops owl, valley of the Rio Porco. phot P. Verbelen

After some 90 years of rumors and speculation, Felipe Spina of Fauna & Flora in Santo Antonio and Philippe Verbelen of Belgium discovered there is, in fact, an owl species living on Príncipe Island! It has finally been seen, photographed (above) and recorded by these gentlemen in the remote southern valley of the Rio Porco, in July, 2016.

Scientists know very little about the new owl beyond discovery that it exists. We do know that the call of the little owl is very different from the call of other known scops species.

The Sao Tome scops owl, Otus hartlaubi. Phot. Hotspot Birding.

But how many owls are there in these rugged, trail-less valleys, and how widely are they distributed on the island? Is it really a new species, genetically distinct from the nearby São Tomé scops owl, Otus hartlaubi? (above) There are three widely distributed species on the mainland, plus two found exclusively in different East African coastal forests (below), and there is another island endemic in the Indian Ocean (Socotra).

Sokoke scops owl, known only from the Arabuko-Sokoke Forest of coastal Kenya. phot. of red phase by Syczek Brunatny.]

How do the Gulf species relate to other scops owls? These basic questions can only be answered by detailed genetic and morphological examination of a live specimen; future work is being planned and led by Dr. Martim Melo of CIBIO, Porto, Portugal, the foremost expert on the birds of São Tomé and Príncipe. Martim first heard this owlet in 1998 and has been searching for it ever since!

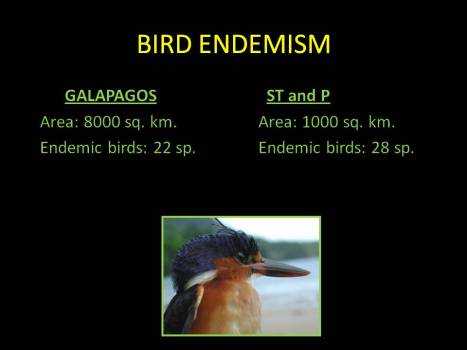

The non-wading bird assemblage of São Tomé and Príncipe may represent the highest level of unique species in the world, by area. Above is an image comparing the bird faunas of the two Gulf islands with the famous Galapagos, a much larger archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean. The Galapagos are justly famous, but it is interesting to note that the majority of endemic bird species there evolved from a very few colonizers; for instance, the celebrated Darwin’s finches are all each others’ closest relatives.

Principe glossy starling, Lamprotornis ornatus. Roca Belo Monte. Phot. P. Loureiro.

The São Tomé and Príncipe avifauna is much richer in different evolutionary lineages; these range from endemic starlings (above), weavers and an oriole to unique sunbirds, kingfishers and flycatchers.

Sao Tome giant weaver. Phot by. Nik Borrow

Among this rich assemblage are several species that are excellent examples of the phenomena of island gigantism and dwarfism discussed in earlier blogs. For instance, the largest weaver bird in the world (70+ species) is the giant weaver (Ploceus grandis, above), endemic to São Tomé. The world’s largest sunbird (Dreptes thomensis, below) is a species also unique to São Tomé.

Sao Tome giant subird. phot. Fabio Olmos

Sunbirds are Old World, nectar-feeding equivalents of the New World hummingbirds. The two groups are not closely related, but they converge greatly in appearance and behavior because they fill the same ecological niche in their respective geographic areas.

Above, the giant sunbird is shown on the right, together with Newton’s sunbird, itself an endemic species; photo taken after banding by Dr. Martim Melo. Like the giant hummingbird of the Andes, the giant hummingbird is also drab in coloration.

São Tomé dwarf ibis. phot. Nik Borrow

There are 27 species of ibis, world-wide; the smallest by far is the São Tomé dwarf ibis, (above, Bostrychia bocagei); there is but a single population of these birds living in the remote southern forest of the big island, and they are severely threatened by poaching for food and the expansion of a large oil palm plantation to the south.

Many of the unique birds on the two islands are singletons; i.e. they are the only representative of their group on one of the two islands, with no relatives on the other.

São Tomé oriole, Oriolus crassirostris.

These endemic flycatchers are also sexually dimorphic]

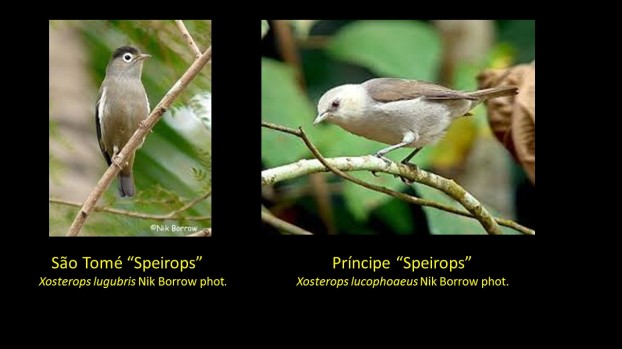

Among the other endemic species are pairs represented by one closely related species on each island. When these species are each other’s closest relatives, they are called “sibling species; however, they can be very similar in appearance and behavior because they fill the same ecological niche on each island- not because they are each others’ closest relatives.

Each island has a thrush species; the Principe thrush (right), newly discovered, is obviously similar and related to that of the big island, but they are not necessarily each others’ closest relatives. Dr. Melo has determined by genetic study that their ancestral colonizers arrived at very different times from the mainland. Recall that Principe is geologically twice as old as Sao Tome. If the ancestor of the thrush on Sao Tome dispersed from Principe, they would be siblings, but as Dr. Melo has shown, both species descended from mainland ancestors at different times.

Many other intriguing bird pairs are found on the islands.

A number of much earlier workers considered some of the islands’ bird species so distinct that they deserved their own generic names, and traditionally, there were seven unique genera recognized on the islands (including the giant sunbird, and Speirops, above). Dr. Melo has shown that even though some of these are dramatically different in appearance from relatives, this similarity is the result of relatively recent selection pressures and genetically, they should still be included within pre-existing genera.

END OF PART I

Here’s the parting shot.

The 2016 education team at Bom Bom island bridge, PrÍncipe Id.: Dr. Maria Jeronimo (left), the author, and Roberta Ayres]

Note: This blog, Part II to follow, is dedicated to the memory of our friend Bill Bowes, of the William K. Bowes Jr. Foundation, who graciously lent his personal encouragement and financial support to and for the GG IX, X and XI expeditions. We of the Gulf of Guinea team and the California Academy of Sciences will miss him very, very much.