A female leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) on Praia Grande, Príncipe island heading back to sea after laying her eggs overnight. Phot. V. Schmitt.

At up to 3 m (9.8 ft) and 932 kg (2,055 lb), the leatherback is the worlds 4th largest reptile (after three crocodile species) and by far the largest turtle.

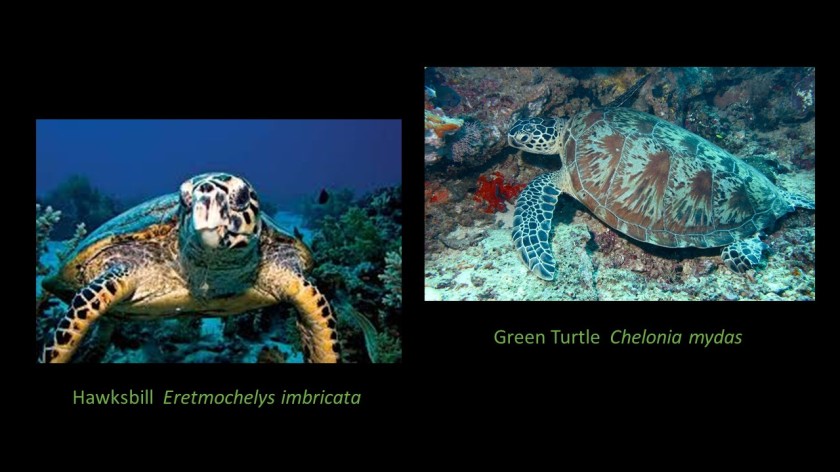

Along with two other marine species (above), the green (Chelonia mydas – inaturalist phot), and the hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata – Brittanica phot.), it breeds annually on certain São Tomé and Príncipe beaches.

Mouth and pharynx of Leatherback. Pinterest phot.

Leatherbacks feed almost exclusively on coelenterates (jellies or jellyfish) and swallowing them is added by long inward-pointing fleshy projections in the throat and pharynx (above). All of the worlds marine turtles are endangered species and the Gulf of Guinea Ids are important sites, guarded and studied by a number of NGO’s including the Príncipe Trust and ATM: the Association for the Protection, Research and Conservation of Sea Turtles in Lusophone countries.

The birds (avifauna) of the two islands are quite remarkable. Combined, São Tomé and Príncipe are only about 1000 km² and yet they are home to 28 unique endemic bird species of many different families. This is the highest density of bird endemism by area in the world. We have also discussed gigantism and dwarfism (above), poorly understood phenomena occurring frequently in island plants and animals.

São Tomé Grosbeak, Neospiza concolor, M. Melo phot and at right.

There have been several recent studies on the islands’ endemic bird species. Dr. Martim Melo of CIBIO, foremost latter-day student of this avifauna has shown that the genetic relationships of the seemingly extremely scarce São Tomé Grosbeak (above) reveal that it is actually a canary, not a grosbeak. It is thus now the world’s largest canary and a true island giant. It is 50% heavier than the next largest related species. As an island giant, it joins other São Tomé giant endemics like the Giant Sunbird, Dreptes thomensis, and the Giant Weave,r Ploceus grandis, the two largest species of their families in the world. These have been featured in earlier blogs. Two additional, less famous São Tomé species are the largest species of their respective families in Africa (above).

São Tomé Speirops, Xosterops lugubris. Phot. Lars Petersson]

SãoTomé Thrush, Turdus olivaceofuscus, Phot. Lars Petersson]

Under different systems, all of the endemic bird species could be considered rare and endangered since each unique species can only have a range of significantly less than 1000 km², which is the area of the two islands combined. In a sense, these unique species could be considered among the rarest in the world. One of the fathers of the “modern synthesis” (evolution + genetics), Prof. Ernst Mayr, wrote a paper in the magazine Science examining the levels of bird endemicity in relationship to island size and distance to mainland source. The extraordinary density of the endemic birds of our islands when compared with predicted levels (below) yield a separate third curve; a phenomenon he simply illustrated but with no attempt to explain it.

The status of nine of the São Tomé endemics is “threatened” according to modern ornithologists; until recently, three of these have been considered “critically endangered”: the São Tomé Grosbeak (above), the Dwarf Olive Ibis and the São Tomé Fiscal Shrike (below)

São Tomé Fiscal Shrike, Lanius newtoni. Phot. L. Petersson

Dwarf Olive Ibis, Bostrychia bocagei. Phot. L. Petersson

A recent paper by Dr. Ricardo de Lima (below) and colleagues is an examination of the ranges and population status of these three endemic birds. They found that the south-west central region of the island, most of which is included in the São Tomé Obô Natural Park, has the highest potential for the Critically Endangered birds, and that indeed all three species were associated with native forest. The ibis prefers high tree density, while the fiscal selects low tree density and intermediate altitudes. “Despite very restricted ranges, population sizes seem to be larger than previously assumed. These results suggest that the fiscal and grosbeak might be better classified as ‘Endangered’, while the ibis should maintain its status under different criteria, due to a very restricted range during the breeding season.”

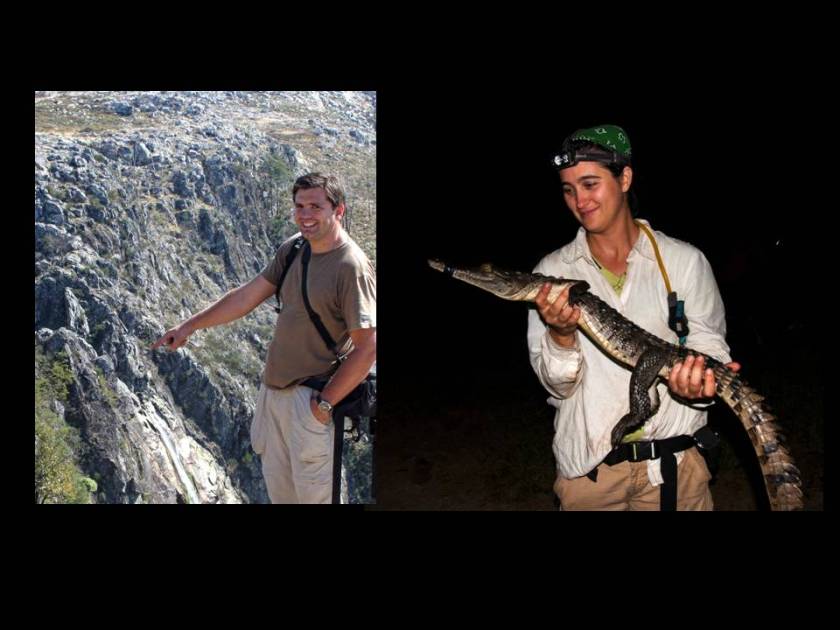

Drs. Rayna Bell, Smithsonian Institution (left) with Dr. Ricardo Lima of University of Lisbon (right)

The colorful and varied endemic bird fauna of São Tomé and Príncipe is a flamboyant if somewhat enigmatic example of speciation and evolution over time. As the graph above illustrates, there are more endemic species by unit area than one would predict, even in light of the near proximity of the African mainland. Although the unique species are now reasonable well-described compared with other elements of the fauna, there is still a great deal to be learned.

The only venomous snake on the islands is the Forest Cobra “Cobra preta”, of São Tomé, fairly common in most inland habitats, and the source of some controversy over the years (see blog, May 2009). Whether it is naturally occurring i.e., the descendent of a disperser like many of the terrestrial uniques, or whether it was brought by man in some manner has been a point of discussion for some years. For a long time the few scientists working on the islands have referred to this species as Naja melanoleuca, a large cobra which is widespread on the African mainland (below).

From blog, May 2008: Within the House of Slytherin II. (left) Naja melanoleuca. Cowyeow photo]

A recent publication by Dr. Luis Ceríaco et al. (National Museum of Natural History and Science) suggests that the São Tomé cobra is a naturally occurring endemic; they have named it Naja peroescobari, after one of the Portuguese navigators who discovered the island in 1471. The authors distinguish Cobra preta from the mainland species by slightly larger size, a different color pattern underneath, and the arrangement of some scales in the throat area.

The São Tomé cobra, Naja escobari. Phot. Tiziano Pisoni, and see Dec. 2013 blog- Another New Species…

While on the subject of reptiles, recent expeditions have afforded us with more knowledge, along with some outstanding new photos of related island endemics:

São Tomé “jita”. Boaedon (Lamprophis sp). Phot Lars Petersson

Príncipe “jita”. Boaedon (Lamprophis sp). Phot. Andrew Stanbridge

We know these two island species are distinct from one another and from close mainland relatives on the basis of pattern and molecular evidence. The big island species (above) has a pattern of lines along the back; that of Príncipe is a series of blotches. A group of us led by Dr. Luis Ceríaco is in the process of assigning new names to these island two populations.

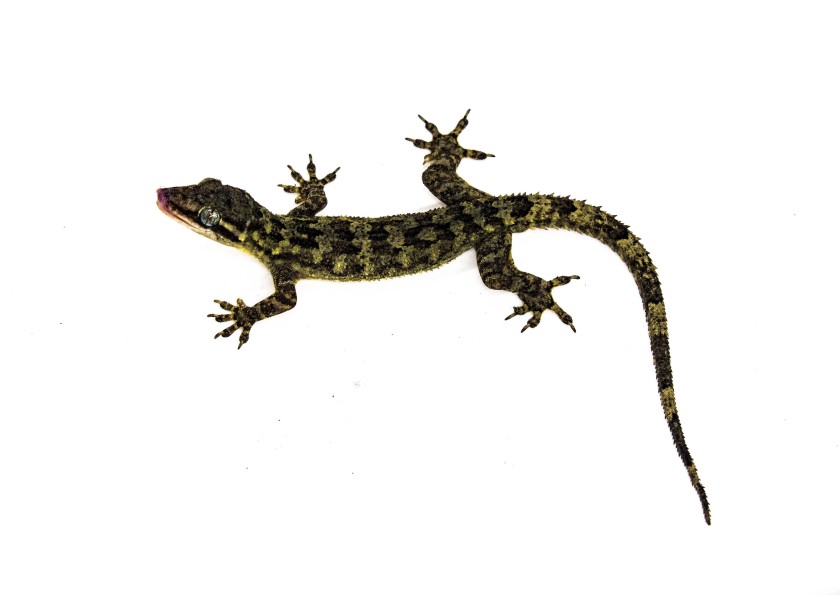

Greef’s Giant gecko, Hemidactylus greefii of São Tomé. A. Stanbridge phot. Note greenish eyes.

Príncipe Giant gecko, H. principensis. R. Bell phot. Note golden eyes.]

Hugulay Maia (insert, below) is a young São Toméan from the big island who has been interested in the natural history of the Gulf of Guinea Islands for most of his life. He and his mentor, the late Angus Gascoigne, have appeared in this blog a number of times over the years, and Hugulay is currently a PhD candidate in marine ecology at the University of Santa Catarina in Brazil. He has just produced a durable guide to the marine species most frequently encountered by local fishermen, pictured below. As a scientist he will be a strong, valuable asset to the islands’ fauna and flora and to the government, especially with respect to the conservation of its natural marine resources.

Quintino Quade (below left) and Genevieve Chase on Macambrara Ridge, São Tomé 2017.

Quade of STeP UP has been a bulwark of our field work and education program since the beginning in 2001. He is a translator, teacher of English and many other useful things. Chase is a consultant from Washington D.C., examining possibilities for expansion and modification of our Gulf of Guinea Project in the future.

The Parting Shot:

Me at Jockey’s Bonnet, Principe Id. This is an ancient island off the east coast that harbors a currently recognized endemic subspecies of finch.

PARTNERS

Our research and educational expeditions are supported by tax-deductable donations to the “California Academy of Sciences Gulf of Guinea Fund*.” We are grateful for ongoing governmental support from the Republic of São Tomé and Príncipe, and especially to Arlindo de Ceita Carvalho, Director General, Victor Bonfim, and Salvador Sousa Pontes of the Ministry of Environment and to Faustino de Oliviera of the Department of Forestry for their continuing authorization to collect and export specimens for study, and to Ned Seligman, Roberta dos Santos, Anita Rodriguez and Quintino Quade of STePUP of Sao Tome, our “home away from home”. GG IX, X and XI were funded in part by a generous grant from The William K. Bowes Jr. Foundation, and substantial donations from Rod C. M. Hall, Mr. and Mrs. Henri Lese, Mr. and Mrs. John L. Sullivan Jr., Mr. and Mrs. John Sears, in memory of Paul Davies Jr. and a heartening number of Bohemian friends. We are grateful for the support of Roça Belo Monte (Africa’s Eden-Príncipe) for both logistics and lodging.

*55 Music Concourse Drive, Golden Gate Park, San Francisco CA 94118 USA

Eurema hecabe

Eurema hecabe